VIVALDI LECTURE

Vivaldi's Four Seasons, Winter

Vivaldi's Four Seasons, Spring

Vivaldi's Women of the Pietà 0-7:00 then 14:30

Other Venice/Vivaldi Youtubes

Venice Night and Day (Today and Yesterday)

Venice Now and Then (0 then 3:40)

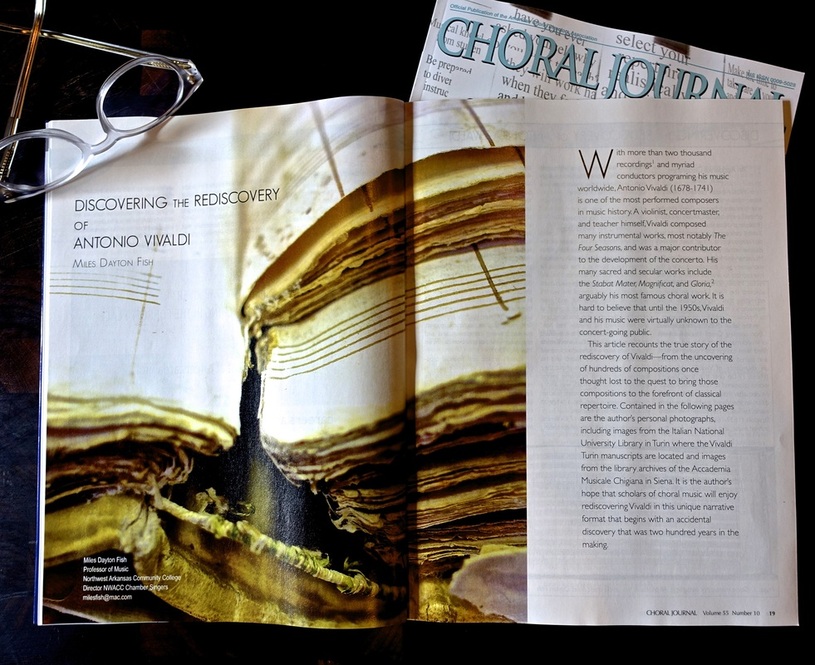

(CLICK here to read the article "Discovering the Rediscovery of Antonio Vivaldi)

V I V A L D I T I M E L I N E

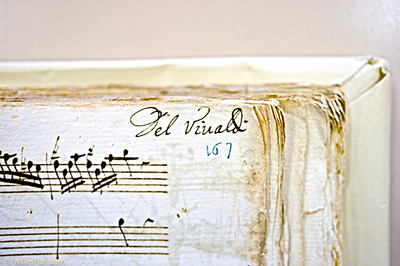

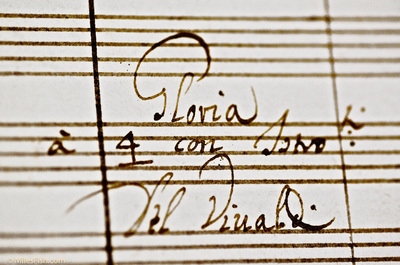

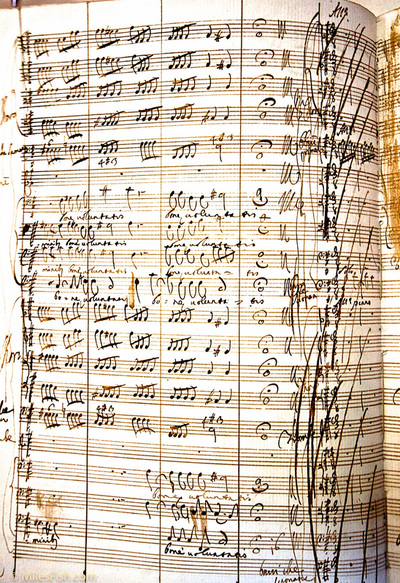

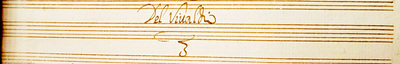

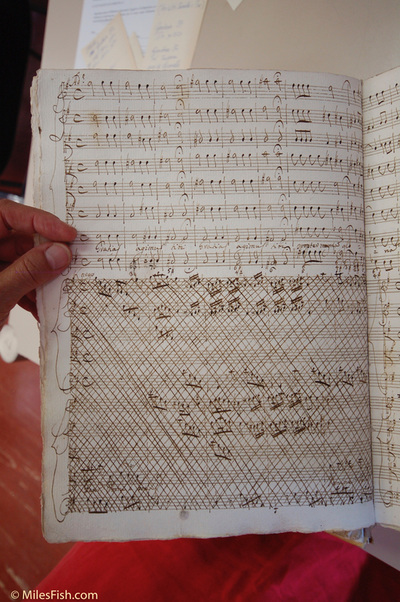

From Discovering the Rediscovery of Antonio Vivaldi

From Discovering the Rediscovery of Antonio Vivaldi

- 1678 – Vivaldi born

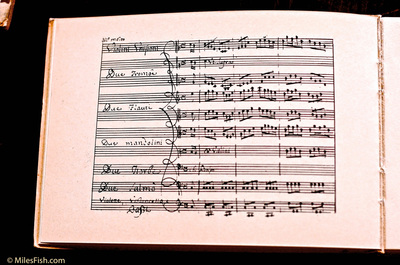

- 1716 – Vivaldi meets Dresden violinist Johann Georg Pisendel in Venice

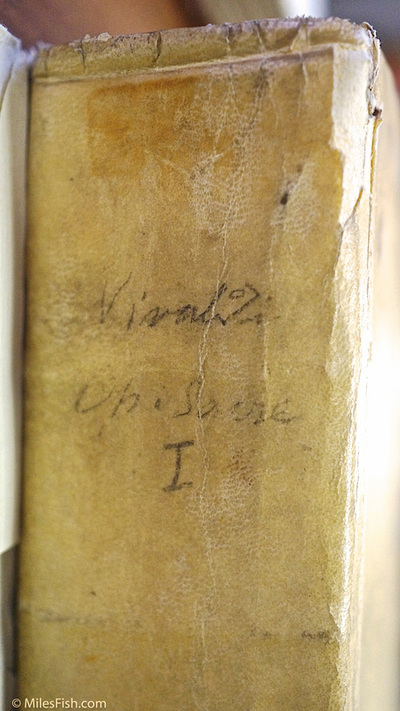

- 1717 – Pisendel returns to Dresden with more than 40 Vivaldi instrumental works

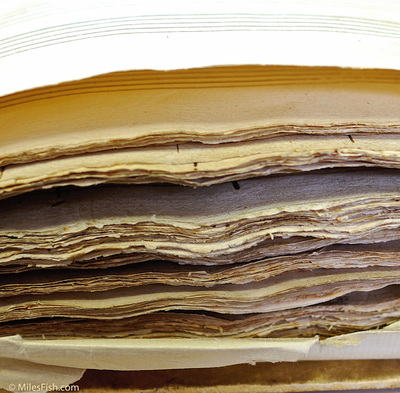

- 1741 – Vivaldi dies and his personal Venice manuscripts are sold to Venetian collector Jacopo Soranzo

- 1755 – Pisendel dies and his library is stored in a large cabinet at Dresden’s Catholic Hofkirche

- 1761 – Jacopo Soranzo dies and his collection of Vivaldi manuscripts is divided

- Late 1700s – Abbot Matteo Luigi Canonici reassembles the Vivaldi manuscripts and sells the collection to Count Giacomo Durazzo

- 1794 – Count Durazzo dies, and the Vivaldi manuscripts are moved from Venice to the Durazzo villa in Genoa

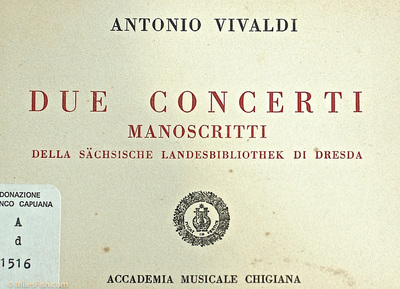

- 1860 – Pisendel’s Vivaldi orchestral manuscripts are discovered in Dresden and moved to the SLUB Dresden

- 1893 – The Durazzo collection is divided between two Durazzo brothers

- 1922 – Marcello Durazzo dies and leaves his collection to the Turin Monastery

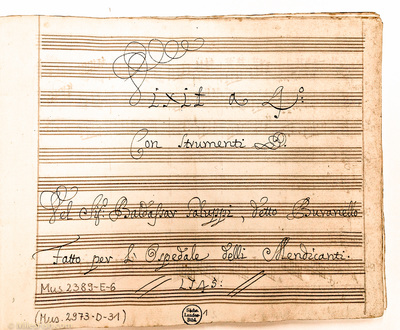

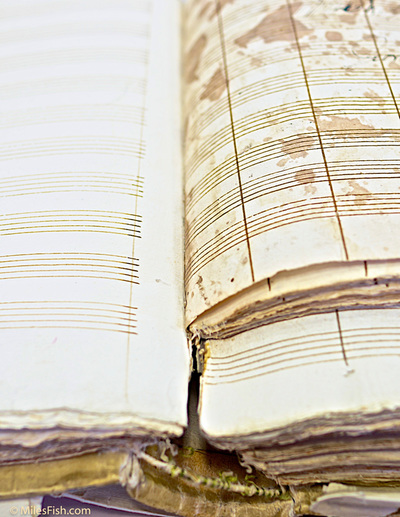

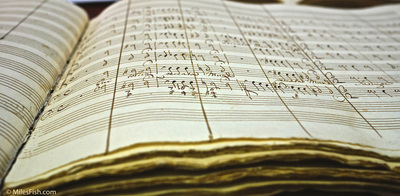

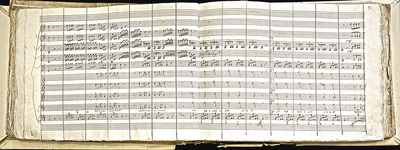

- 1926 – Monks at the Turin Monastery send Vivaldi manuscripts to Professor Alberto Gentili

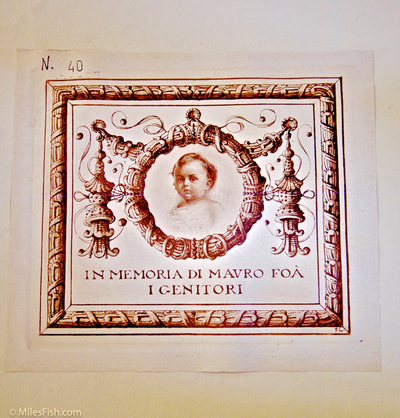

- 1927 – Roberto Foà purchases and donates Vivaldi Turin manuscripts to the Turin Library in memory of his deceased infant son, Mauro

- 1927 – The second half of the Durazzo Vivaldi manuscripts are discovered in the possession of Giuseppe Maria Durazzo

- 1930 – Giuseppe Maria gives permission to sell his manuscripts to the Turin Library

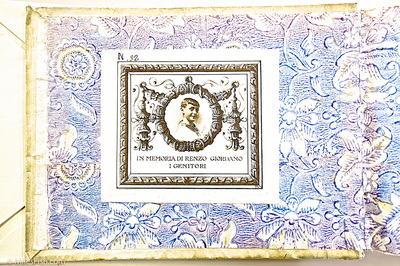

- 1930 – Filippo Giordano purchases Durazzo manuscripts and donates the collection to the Turin Library

- October 30, 1930 – The Vivaldi collection is complete

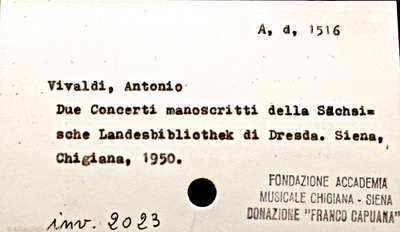

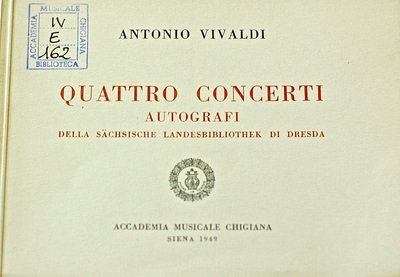

- 1933 – Olga Rudge begins working for Count Guido Chigi Saracini at the Accademia Musicale Chigiana

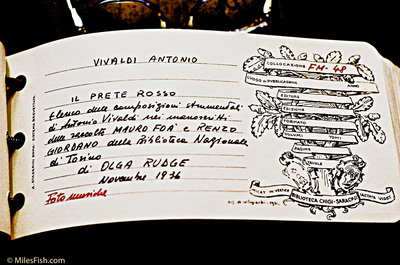

- 1935-1936 – Olga Rudge travels to Turin to examine and catalogue the Vivaldi manuscripts

- 1938 – The Durazzo stipulation of “no practice/no performance” is lifted

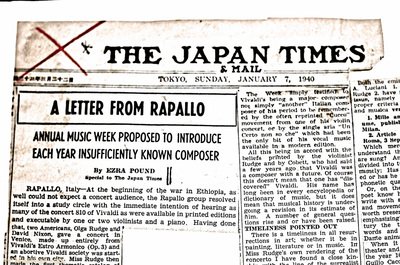

- 1938 – Ezra Pound transcribes microfilms of the Vivaldi manuscripts from the Dresden library for performance at Rapallo concerts

- 1938 – Olga Rudge establishes Centro di Studi Vivaldiani in Siena

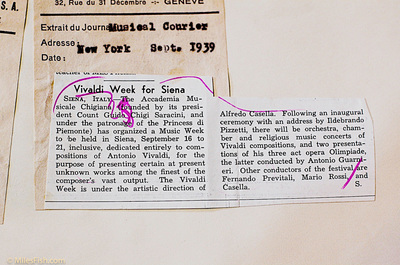

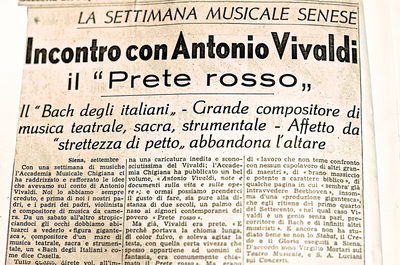

- September 16-21, 1939 – Vivaldi Festival Week in Siena

- September 27, 1939 – Warsaw surrenders to Germany in WWII

- June 1940 – The Turin Library is damaged in air raids

- December 1942-April 1943 – Historical documents and music manuscripts are moved from the Turin Library to the Castle of Montiglio d’Asti

- 1945 – Manuscripts at the Castle of Monti- glio d’Asti are returned to the Turin Library

- 1945 – Dresden is bombed and some Vivaldi manuscripts are damaged

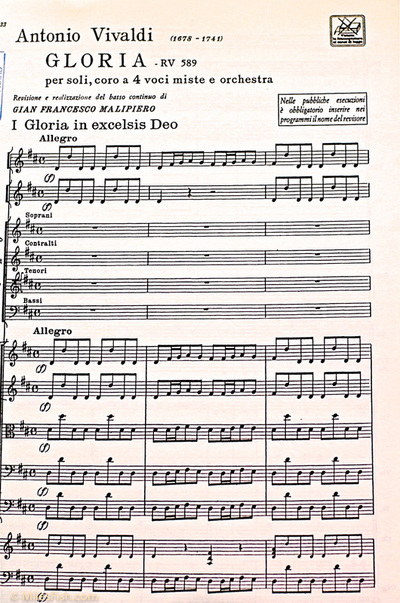

- 1947 – Italian Antonio Vivaldi Institute is founded in Venice by Antonio Fanna

- December 31, 1947 – Louis Kaufman debuts a portion of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons at Carnegie Hall

- 1951 – Kaufman launches a series of all-Vivaldi concerts

- 2015 – Vivaldi continues to be one of the most performed and recorded composers in history

V E N I C E

D R E S D E N

V I E N N A

S I E N A

T U R I N

Naxos Article about the Four Seasons

VIVALDI: The Four Seasons

Louis Kaufman (violin), Peter Rybar (violin), Concert Hall Chamber Orchestra, Henry Swoboda,

“The Masterpiece That Took 200 Years to Become Timeless” by Jeremy Eichler

The New York Times, Sunday, February 27th, 2005

Ah, the timeless masterpiece. The very phrase reveals our unspoken assumptions. With works like Beethoven's Fifth Symphony or Vivaldi's "Four Seasons," their merit is so manifest, their greatness so pristinely enshrined that we tend to imagine them existing outside history, as unbounded by time as the genius of their creators.

What a pleasure, then, to come across a new Naxos Historical release: the first American recording of Vivaldi's "Four Seasons," performed by Louis Kaufman, a well-traveled soloist and ubiquitous concertmaster during the golden age of Hollywood film scores. (You've probably heard him even if you never knew it.) Kaufman is backed by the Concert Hall Chamber Orchestra, under Henry Swoboda. But the salient detail is the recordings' amazingly late date: 1948. Believe it or not, the timeless Vivaldi had been an obscure composer in America all the way through World War II. He was studied by scholars mostly for what he taught us about Bach. Performances were scarce, and the public knew little of his music.

Fast-forward roughly half a century, and these four Vivaldi concertos are perhaps the single greatest hit of classical music. They have been recorded more than 100 times and by most respectable violinists of recent decades; they have been used in Hollywood movies like "Pretty Woman" and in television commercials to hawk sundry products from cars to credit cards. They grace elevators and hotel lobbies across the land, and in what is perhaps the ultimate test of classical hit status, they have even been transmogrified into ring tones for cellphones. If you're a classical melody, that's when you know you've really made it.

So what exactly happened to "The Four Seasons"? How and why did these concertos take off, and what has been the price of popularity? Answers are elusive, but like most explosions in popularity, this one owes a lot to happy timing. At least in this country, the story began one day late in 1947, when Kaufman received a call from a CBS executive inviting him to perform the "Four Seasons" concertos for radio broadcast.

Kaufman, who was born in 1905 in Portland, Ore., was living in Los Angeles at the time, playing with studio orchestras while maintaining a simultaneous career as a concert soloist. Time was scarce, and shortly after deciding to record the Vivaldi concertos in Carnegie Hall, he left by train for New York along with his wife, Annette. He learned the solo part en route, unraveling the music's mysteries as the landscape streamed by.

"We fell in love with the pieces while he was learning them on that train," Ms. Kaufman said recently from her home in Los Angeles. "They just seemed so fresh and unexpected. We couldn't get over the wonderful melodies."

Once Kaufman arrived in New York, there was little time to linger over details. He was racing to record the pieces before a union recording ban took effect on Jan. 1, 1948. Carnegie Hall was booked solid with other groups also seeking to beat the deadline, so Kaufman, along with Swoboda and a small orchestra made up mostly of New York Philharmonic players, took the hall the last four nights of the year, starting each session at midnight. In his memoirs, "A Fiddler's Tale," Kaufman describes working into the early morning hours in the darkened hall, with the stage brightly lighted. Annette turned pages, and the fatigued musicians, who had been recording with Stokowski in addition to playing their own concerts, stayed attentive, thanks to this new and strangely beguiling music.

The recording that emerged is a fine one, full of high-flown Romantic playing that is enjoyably oblivious to Baroque performance style and peppered with its own version of "period" effects: principally, the swooping portamentos of the mid-20th century.

The Naxos two-disc reissue also includes Kaufman's later recording of the other eight concertos in the Opus 8 set.

Sticklers for accuracy will take issue with Naxos's trumpeted claim that this is the world premiere recording of "The Four Seasons." The Italian conductor Bernardino Molinari recorded the concertos five years earlier, in 1942. The restoration producers defend their claim by explaining that Kaufman used a more accurate edition of the score, whereas Molinari's recordings were based on his own liberal transcriptions.

Whatever the case, there's no doubt that Kaufman's "Four Seasons" was the first complete American recording. It was released by Concert Hall Society and favorably reviewed in The New York Times in October 1948. The Times critic Howard Taubman introduced the piece to his readers as "an early and delightful experiment in program music."

At the same time, Vivaldi's fortunes were buoyed by an event that did wonders for Baroque music: the introduction of the LP. Smaller record companies like Vox and Concert Hall scrambled to record Baroque repertory that had been overlooked by the major labels. The new technology and the smaller orchestras required for Baroque music meant that recordings could be made more cheaply. They sold well, too.

"Sam Goody couldn't keep the records in stock," Peter Munves, a longtime record collector and industry executive, said recently. "It was new stuff. It was exciting."

Gene Bruck, another avid collector, remembers "The Four Seasons" as his first LP: "We thought not only was this sensational music, but you could actually play the whole thing. Everyone bought it, and boom, off it went."

The newly released Baroque music also fell on receptive ears. One could argue that the music's lightness and transparency, its distance from a freshly tainted German Romanticism, made it perfectly suited to American life in the postwar decade of the 1950's. Other violinists soon got into the act, recording their own versions of the "Seasons." Italian ensembles like I Virtuosi di Roma and I Musici spread the word, and did so with a pioneering awareness of historic style.

Of course, timing is only part of the story. At a more basic level, "The Four Seasons" was - and is - extraordinarily original music, full of brilliant and glistening sonorities, ingenious formal innovations and all those vivid solo lines bursting off the page.

And perhaps most important for its popular appeal, "The Four Seasons" has a program that incorporates the most basic human elements: the world of nature, the cycle of the years, the passage of time.

Seasonal sounds and images are inscribed into the music, yet the work's program does not constrain the imagination. Rather, each season provides a ready-made point of departure for a wide range of metaphors. It was no doubt in this spirit that Alan Alda chose the work as a poetic template for his 1981 film "The Four Seasons," about the intertwined lives of three couples and their travels in summer, fall, winter and spring.

On the flip side, the work's instant recognizability, coupled with its classical pedigree, has made it a handy marketing tool. "There is an association with luxury and with elegance that is very clear," said Nick Hahn, the managing director of Vivaldi Partners, a marketing strategy consulting firm.

Classical hits like "The Four Seasons" also loom large in the endless barrage of "lifestyle-oriented" CD releases. A recent search on Amazon.com produced a whopping 794 hits. Of these, the great majority are compilations, some with eminently quotable titles.

Hoping to bring a touch of class to that French toast? Try "CBS Masterworks Dinner Classics: Sunday Brunch, Volume 2." Tired of bathing in silence? Now there's "Baroque at Bathtime: A Relaxing Serenade to Wash Your Cares Away." (I promise, I'm not making this up.) Or finally, a personal favorite that cuts right to the chase: "The Only Classical CD You'll Ever Need."

That last title touches on a more serious problem in the way classical hits can crowd out too much other music. Vivaldi wrote dozens of worthy violin concertos that get barely a nod. Moreover, the heavy rotation of masterpieces tends to numb our ears, making it hard to hear them fresh. If only this music could take a vacation, or if performers could call a moratorium for the sake of Vivaldi's future.

At least there are still bracing contemporary releases like Gidon Kremer's version (on Nonesuch) that blast away habits of complacent listening and open the ears once more to Vivaldi's radical imagination. I like Kaufman's version, too, for the way it can accomplish a similar effect - not through the playing itself, but through the niche it occupies in the past.

Just as historians are challenged to write history as if they didn't know what was coming next, those who approach historic recordings can strive to listen through ears of decades past, forgetting what they know of the intervening years. Yes, of course, it's an illusion, but it can be a productive one.

Imagine: it is 1948. A new set of records has just arrived bearing the curious promise of music for each season. The textures are brilliant, the writing is breathtakingly original and the solo playing sings. You know, this Vivaldi - he just might have some potential.

VIVALDI: The Four Seasons

Louis Kaufman (violin), Peter Rybar (violin), Concert Hall Chamber Orchestra, Henry Swoboda,

“The Masterpiece That Took 200 Years to Become Timeless” by Jeremy Eichler

The New York Times, Sunday, February 27th, 2005

Ah, the timeless masterpiece. The very phrase reveals our unspoken assumptions. With works like Beethoven's Fifth Symphony or Vivaldi's "Four Seasons," their merit is so manifest, their greatness so pristinely enshrined that we tend to imagine them existing outside history, as unbounded by time as the genius of their creators.

What a pleasure, then, to come across a new Naxos Historical release: the first American recording of Vivaldi's "Four Seasons," performed by Louis Kaufman, a well-traveled soloist and ubiquitous concertmaster during the golden age of Hollywood film scores. (You've probably heard him even if you never knew it.) Kaufman is backed by the Concert Hall Chamber Orchestra, under Henry Swoboda. But the salient detail is the recordings' amazingly late date: 1948. Believe it or not, the timeless Vivaldi had been an obscure composer in America all the way through World War II. He was studied by scholars mostly for what he taught us about Bach. Performances were scarce, and the public knew little of his music.

Fast-forward roughly half a century, and these four Vivaldi concertos are perhaps the single greatest hit of classical music. They have been recorded more than 100 times and by most respectable violinists of recent decades; they have been used in Hollywood movies like "Pretty Woman" and in television commercials to hawk sundry products from cars to credit cards. They grace elevators and hotel lobbies across the land, and in what is perhaps the ultimate test of classical hit status, they have even been transmogrified into ring tones for cellphones. If you're a classical melody, that's when you know you've really made it.

So what exactly happened to "The Four Seasons"? How and why did these concertos take off, and what has been the price of popularity? Answers are elusive, but like most explosions in popularity, this one owes a lot to happy timing. At least in this country, the story began one day late in 1947, when Kaufman received a call from a CBS executive inviting him to perform the "Four Seasons" concertos for radio broadcast.

Kaufman, who was born in 1905 in Portland, Ore., was living in Los Angeles at the time, playing with studio orchestras while maintaining a simultaneous career as a concert soloist. Time was scarce, and shortly after deciding to record the Vivaldi concertos in Carnegie Hall, he left by train for New York along with his wife, Annette. He learned the solo part en route, unraveling the music's mysteries as the landscape streamed by.

"We fell in love with the pieces while he was learning them on that train," Ms. Kaufman said recently from her home in Los Angeles. "They just seemed so fresh and unexpected. We couldn't get over the wonderful melodies."

Once Kaufman arrived in New York, there was little time to linger over details. He was racing to record the pieces before a union recording ban took effect on Jan. 1, 1948. Carnegie Hall was booked solid with other groups also seeking to beat the deadline, so Kaufman, along with Swoboda and a small orchestra made up mostly of New York Philharmonic players, took the hall the last four nights of the year, starting each session at midnight. In his memoirs, "A Fiddler's Tale," Kaufman describes working into the early morning hours in the darkened hall, with the stage brightly lighted. Annette turned pages, and the fatigued musicians, who had been recording with Stokowski in addition to playing their own concerts, stayed attentive, thanks to this new and strangely beguiling music.

The recording that emerged is a fine one, full of high-flown Romantic playing that is enjoyably oblivious to Baroque performance style and peppered with its own version of "period" effects: principally, the swooping portamentos of the mid-20th century.

The Naxos two-disc reissue also includes Kaufman's later recording of the other eight concertos in the Opus 8 set.

Sticklers for accuracy will take issue with Naxos's trumpeted claim that this is the world premiere recording of "The Four Seasons." The Italian conductor Bernardino Molinari recorded the concertos five years earlier, in 1942. The restoration producers defend their claim by explaining that Kaufman used a more accurate edition of the score, whereas Molinari's recordings were based on his own liberal transcriptions.

Whatever the case, there's no doubt that Kaufman's "Four Seasons" was the first complete American recording. It was released by Concert Hall Society and favorably reviewed in The New York Times in October 1948. The Times critic Howard Taubman introduced the piece to his readers as "an early and delightful experiment in program music."

At the same time, Vivaldi's fortunes were buoyed by an event that did wonders for Baroque music: the introduction of the LP. Smaller record companies like Vox and Concert Hall scrambled to record Baroque repertory that had been overlooked by the major labels. The new technology and the smaller orchestras required for Baroque music meant that recordings could be made more cheaply. They sold well, too.

"Sam Goody couldn't keep the records in stock," Peter Munves, a longtime record collector and industry executive, said recently. "It was new stuff. It was exciting."

Gene Bruck, another avid collector, remembers "The Four Seasons" as his first LP: "We thought not only was this sensational music, but you could actually play the whole thing. Everyone bought it, and boom, off it went."

The newly released Baroque music also fell on receptive ears. One could argue that the music's lightness and transparency, its distance from a freshly tainted German Romanticism, made it perfectly suited to American life in the postwar decade of the 1950's. Other violinists soon got into the act, recording their own versions of the "Seasons." Italian ensembles like I Virtuosi di Roma and I Musici spread the word, and did so with a pioneering awareness of historic style.

Of course, timing is only part of the story. At a more basic level, "The Four Seasons" was - and is - extraordinarily original music, full of brilliant and glistening sonorities, ingenious formal innovations and all those vivid solo lines bursting off the page.

And perhaps most important for its popular appeal, "The Four Seasons" has a program that incorporates the most basic human elements: the world of nature, the cycle of the years, the passage of time.

Seasonal sounds and images are inscribed into the music, yet the work's program does not constrain the imagination. Rather, each season provides a ready-made point of departure for a wide range of metaphors. It was no doubt in this spirit that Alan Alda chose the work as a poetic template for his 1981 film "The Four Seasons," about the intertwined lives of three couples and their travels in summer, fall, winter and spring.

On the flip side, the work's instant recognizability, coupled with its classical pedigree, has made it a handy marketing tool. "There is an association with luxury and with elegance that is very clear," said Nick Hahn, the managing director of Vivaldi Partners, a marketing strategy consulting firm.

Classical hits like "The Four Seasons" also loom large in the endless barrage of "lifestyle-oriented" CD releases. A recent search on Amazon.com produced a whopping 794 hits. Of these, the great majority are compilations, some with eminently quotable titles.

Hoping to bring a touch of class to that French toast? Try "CBS Masterworks Dinner Classics: Sunday Brunch, Volume 2." Tired of bathing in silence? Now there's "Baroque at Bathtime: A Relaxing Serenade to Wash Your Cares Away." (I promise, I'm not making this up.) Or finally, a personal favorite that cuts right to the chase: "The Only Classical CD You'll Ever Need."

That last title touches on a more serious problem in the way classical hits can crowd out too much other music. Vivaldi wrote dozens of worthy violin concertos that get barely a nod. Moreover, the heavy rotation of masterpieces tends to numb our ears, making it hard to hear them fresh. If only this music could take a vacation, or if performers could call a moratorium for the sake of Vivaldi's future.

At least there are still bracing contemporary releases like Gidon Kremer's version (on Nonesuch) that blast away habits of complacent listening and open the ears once more to Vivaldi's radical imagination. I like Kaufman's version, too, for the way it can accomplish a similar effect - not through the playing itself, but through the niche it occupies in the past.

Just as historians are challenged to write history as if they didn't know what was coming next, those who approach historic recordings can strive to listen through ears of decades past, forgetting what they know of the intervening years. Yes, of course, it's an illusion, but it can be a productive one.

Imagine: it is 1948. A new set of records has just arrived bearing the curious promise of music for each season. The textures are brilliant, the writing is breathtakingly original and the solo playing sings. You know, this Vivaldi - he just might have some potential.

_____________________________________________________

CLICK for "Discovering the Rediscovery of Antonio Vivaldi" by Miles Fish

"Music and other Arts of War" by Miles Fish

Screenplay

Historical Fiction WWII Resistance and the rediscovery of Antonio Vivaldi

CLICK BELOW

Screenplay

Historical Fiction WWII Resistance and the rediscovery of Antonio Vivaldi

CLICK BELOW