American Music

Americans have been singing since the first Europeans and Africans began arriving in North America in the sixteenth century. Work songs, hymns, love songs, dance tunes, humorous songs, and parodies—such songs provide a record of American history, serving both as historical sources and also as subjects of historical investigation.

During the colonial, revolutionary, and federal periods (1607-1820) most American songs were strongly tied to the musical traditions of the British isles. Hymn tunes, ballads, theater songs, and drinking songs were imported from England or based closely on English models. The main exceptions were the hymns of German-speaking communities in Pennsylvania, the music of African-American slave communities, and the songs of New Orleans, which were closely linked to the French West Indies and to France. Those exceptions aside, the most distinctively American songs were patriotic ones, like “Yankee Doodle” and the “Star Spangled Banner,” and even these were adaptations of English originals.

The first uniquely American popular song tradition arose with the minstrel show, beginning in the 1840s. Many songs still familiar today, such as “Turkey in the Straw” (“Zip Coon”) (c. 1824), “Oh Susanna” (1854), “Dixie” (1859), “Buffalo Gals” (1844), and “Old Folks at Home” ("Swanee River") (1851), were originally composed for the minstrel stage and first performed on northern stages by white singers in blackface. These blackface performers adopted and exaggerated the styles of African-American song and movement in a politically charged process. After the Civil War, African-American performers were only able to establish a toehold in the entertainment industry by conforming to the still popular, and demeaning, forms that originated with white performers in blackface.

African Americans themselves created all-black minstrel shows, contributing songs like “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” (1878) and “O Dem Golden Slippers” (1879) to the repertory. European songs, especially sentimental songs like those contained in Moore’s Irish Melodies (1808-1834) and arias from Italian operas, remained important in the first half of the nineteenth century, joined by similar songs composed in America, for example “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair” (1854), “Lorena” (1857), and “Aura Lee” (1861), recorded with new lyrics in 1956 by Elvis Presley as “Love Me Tender.”

American song in the second half of the nineteenth century underwent a tremendous commercial expansion, which extended into the twentieth century and indeed has not abated today. Initially, sheet music and pocket songsters were the primary means of circulating songs, since many Americans played and sang music in their own homes. The music publishing industry was increasingly concentrated in New York City’s famous “Tin Pan Alley” by the 1880s. After that point, however, songs also came to be bought, sold, and preserved in a succession of new media: sound recordings and player pianos in the 1890s; radio in the 1920s, movie sound tracks in the late 1920s, television in the 1950s, cassette tapes in the early 1960s, CDs in the early 1980s, DVDs in the mid 1990s, and MP3s in the late 1990s. This commercial expansion meant that more songs were composed, performed, produced, and consumed in the United States, as well as exported to, and received from, the rest of the world.

Expansion and commercialization extended a process that began with the minstrel show: songs that had once been restricted to ethnic minorities or immigrant groups were marketed to the entire nation. Irish ballads like “Danny Boy” (1913), “My Wild Irish Rose” (1899), and "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling" (1913) became popular among non-Irish singers and listeners; so did Italian songs like “O Sole Mio” (1899). Jewish composers and performers likewise incorporated elements from their culture into American music, as when Sophie Tucker alternately sang her popular “My Yiddishe Momme” (1925) in English and Yiddish. African-American traditions gave rise to a succession of distinctive song styles: spirituals, ragtime, blues, and, later, rhythm and blues, all appropriated enthusiastically by white American performers and audiences.

This was not simply a matter of cross-marketing or trading repertories. Songwriters and performers from a wide range of backgrounds listened to each other’s music, learned from it, parodied it, created new styles out of it, and crossed back and forth between musical genres. By the 1970s, for example, an African-American performer like Ray Charles, deeply rooted in black religious music, the blues, and rhythm and blues, could easily take a country music song like “You Are My Sunshine” (1940) or a sentimental ballad like “Georgia on My Mind” (1930) and make them his own.

By the 1950s two different, seemingly contradictory, things were coming to be true about American popular music. The first is that some songs remained familiar across long periods of time and to very different people. A so-called “standard”—a song from Tin Pan Alley’s glory days (roughly 1910 to 1954)—might be recorded hundreds of times over several decades and remain familiar today. “St. Louis Blues” (1914), “Stardust” (1929), and “God Bless America” (1939) are still with us, in multiple versions. At the same time, with the rise of rock ‘n roll in the 1950s and the great commercial success of African-American rhythm and blues and soul music in the following decade, taste in popular song was increasingly separated by age, race, ethnicity, region, and gender. Perhaps the best sign of this is the proliferation of musical categories in record stores and in music award shows.

These seemingly contrary tendencies may well be two sides of the same coin and part of a long-standing process in American music. For at least the past two centuries, much of what is dynamic in American music arose out of a continual process of sampling, fusing, and appropriating the different musics that make up American popular song. Commercial music industries, from live entertainment to sheet music to recordings, while catering to mainstream audiences, have also sought out musical styles and performers from beyond the mainstream. Marginalized by factors such as geography, race, and economic class, performers and styles such as “hillbilly” or country music, delta blues, and hip hop have worked their way onto stages and into recording booths throughout the history of American popular song.

Below--Part 1 and Part 2--is an progressive History Anthology of American Tunes.

Scroll through and listen to EACH selection.

THEN move to American Classical Music Section and listen to Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue.

During the colonial, revolutionary, and federal periods (1607-1820) most American songs were strongly tied to the musical traditions of the British isles. Hymn tunes, ballads, theater songs, and drinking songs were imported from England or based closely on English models. The main exceptions were the hymns of German-speaking communities in Pennsylvania, the music of African-American slave communities, and the songs of New Orleans, which were closely linked to the French West Indies and to France. Those exceptions aside, the most distinctively American songs were patriotic ones, like “Yankee Doodle” and the “Star Spangled Banner,” and even these were adaptations of English originals.

The first uniquely American popular song tradition arose with the minstrel show, beginning in the 1840s. Many songs still familiar today, such as “Turkey in the Straw” (“Zip Coon”) (c. 1824), “Oh Susanna” (1854), “Dixie” (1859), “Buffalo Gals” (1844), and “Old Folks at Home” ("Swanee River") (1851), were originally composed for the minstrel stage and first performed on northern stages by white singers in blackface. These blackface performers adopted and exaggerated the styles of African-American song and movement in a politically charged process. After the Civil War, African-American performers were only able to establish a toehold in the entertainment industry by conforming to the still popular, and demeaning, forms that originated with white performers in blackface.

African Americans themselves created all-black minstrel shows, contributing songs like “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” (1878) and “O Dem Golden Slippers” (1879) to the repertory. European songs, especially sentimental songs like those contained in Moore’s Irish Melodies (1808-1834) and arias from Italian operas, remained important in the first half of the nineteenth century, joined by similar songs composed in America, for example “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair” (1854), “Lorena” (1857), and “Aura Lee” (1861), recorded with new lyrics in 1956 by Elvis Presley as “Love Me Tender.”

American song in the second half of the nineteenth century underwent a tremendous commercial expansion, which extended into the twentieth century and indeed has not abated today. Initially, sheet music and pocket songsters were the primary means of circulating songs, since many Americans played and sang music in their own homes. The music publishing industry was increasingly concentrated in New York City’s famous “Tin Pan Alley” by the 1880s. After that point, however, songs also came to be bought, sold, and preserved in a succession of new media: sound recordings and player pianos in the 1890s; radio in the 1920s, movie sound tracks in the late 1920s, television in the 1950s, cassette tapes in the early 1960s, CDs in the early 1980s, DVDs in the mid 1990s, and MP3s in the late 1990s. This commercial expansion meant that more songs were composed, performed, produced, and consumed in the United States, as well as exported to, and received from, the rest of the world.

Expansion and commercialization extended a process that began with the minstrel show: songs that had once been restricted to ethnic minorities or immigrant groups were marketed to the entire nation. Irish ballads like “Danny Boy” (1913), “My Wild Irish Rose” (1899), and "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling" (1913) became popular among non-Irish singers and listeners; so did Italian songs like “O Sole Mio” (1899). Jewish composers and performers likewise incorporated elements from their culture into American music, as when Sophie Tucker alternately sang her popular “My Yiddishe Momme” (1925) in English and Yiddish. African-American traditions gave rise to a succession of distinctive song styles: spirituals, ragtime, blues, and, later, rhythm and blues, all appropriated enthusiastically by white American performers and audiences.

This was not simply a matter of cross-marketing or trading repertories. Songwriters and performers from a wide range of backgrounds listened to each other’s music, learned from it, parodied it, created new styles out of it, and crossed back and forth between musical genres. By the 1970s, for example, an African-American performer like Ray Charles, deeply rooted in black religious music, the blues, and rhythm and blues, could easily take a country music song like “You Are My Sunshine” (1940) or a sentimental ballad like “Georgia on My Mind” (1930) and make them his own.

By the 1950s two different, seemingly contradictory, things were coming to be true about American popular music. The first is that some songs remained familiar across long periods of time and to very different people. A so-called “standard”—a song from Tin Pan Alley’s glory days (roughly 1910 to 1954)—might be recorded hundreds of times over several decades and remain familiar today. “St. Louis Blues” (1914), “Stardust” (1929), and “God Bless America” (1939) are still with us, in multiple versions. At the same time, with the rise of rock ‘n roll in the 1950s and the great commercial success of African-American rhythm and blues and soul music in the following decade, taste in popular song was increasingly separated by age, race, ethnicity, region, and gender. Perhaps the best sign of this is the proliferation of musical categories in record stores and in music award shows.

These seemingly contrary tendencies may well be two sides of the same coin and part of a long-standing process in American music. For at least the past two centuries, much of what is dynamic in American music arose out of a continual process of sampling, fusing, and appropriating the different musics that make up American popular song. Commercial music industries, from live entertainment to sheet music to recordings, while catering to mainstream audiences, have also sought out musical styles and performers from beyond the mainstream. Marginalized by factors such as geography, race, and economic class, performers and styles such as “hillbilly” or country music, delta blues, and hip hop have worked their way onto stages and into recording booths throughout the history of American popular song.

Below--Part 1 and Part 2--is an progressive History Anthology of American Tunes.

Scroll through and listen to EACH selection.

THEN move to American Classical Music Section and listen to Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue.

Face to Face class: American Music (over-simplified)

East USA: Music in NYC

European Songs / English, German, Italian, Irish, French

NYC European Neighborhoods: Folk Songs / Opera / Symphonies / Parlor Songs / Tin Pan Alley / Sheet Music

South USA: Music in New Orleans

Africa, Caribbean & West Indies, S/Cen. America

African Americans: Worksongs, Spirituals, Blues, RagTime

*Jazz*

Mixed Neighborhoods / Jim Crow

Minstrel shows

Central USA: European Folk Songs / Bluegrass & Country Western

1900s Sheet Music / Tin Pan Alley / Minstral Shows

1920s Radio

1930s Movies

1950s TV

East USA: Music in NYC

European Songs / English, German, Italian, Irish, French

NYC European Neighborhoods: Folk Songs / Opera / Symphonies / Parlor Songs / Tin Pan Alley / Sheet Music

South USA: Music in New Orleans

Africa, Caribbean & West Indies, S/Cen. America

African Americans: Worksongs, Spirituals, Blues, RagTime

*Jazz*

Mixed Neighborhoods / Jim Crow

Minstrel shows

Central USA: European Folk Songs / Bluegrass & Country Western

1900s Sheet Music / Tin Pan Alley / Minstral Shows

1920s Radio

1930s Movies

1950s TV

Face to Face classes and OnLine classes

Anthology of American Popular Tunes

PART I

1. "I Dream of Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair" (:20)

2. "Hoe Emma Hoe"

3. "Cross Roads" Robert Johnson (:10)

"Cross Roads" Clapton/Mayer (09)

"Sweete Home Chicago" Robert Johnson

"Sweet Home Chicato" Bonnie Raitt and friends (:28)

4. Early African American spiritual

4b. Later Afrcican American spiritual

4c. Still later...

4d. And today ("30)

5. African American Gospel

6. "O Happy Day"--More Gospel--Hawkins Singers (:20)

7. "The Entertainer"--Scott Joplin--RagTime

"Maple Leaf Rag--Scott Joplin--RagTime

8. Clarence Williams--Early Dixieland

9. "Ain't Misbehavin'"--Fats Waller Early Jazz

10. "Roll Over Beethoven"--Chuck Berry--Early African American Rock 'n Roll (:45)

11. "Rock Around the Clock"--Bill Haley and his Comets--Early Caucasian Rock 'n Roll--Bill Haley and his Comets

12. "Hound Dog"--Early Elvis (30)

13. "Hound Dog"--Big Mamma Thornton (23)

PART II

14. Sweet Little Sixteen (:05)

15. Surfin USA

16. Hold On I'm Comin'

17. New Bag / Feel Good (:10)

18. Respect Otis Redding (:10)

"Try a Little Tenderness" Otis Redding (:12)

"Sitting on the Dock of the Bay" Otis Redding

"Sitting on the Dock of the Bay" Chicago Group

19. Respect II

20. Prayer for You (:10)

21. At Last (:17)

22. You Keep Me Hangin' On

23 He Stopped Loving Her Today (:20)

24. DIVORCE

25. Tutti Frutti

26. Tutti Frutti II

27. Good Golly Miss Molly

28. Good Golly Miss Molly II

29. Good Golly Miss Molly III

30. She Loves You

31. Satisfaction

32. Honky Tonk Woman (:20)

33. Robert Johnson (XRoads)

34. Eric Clapton (XRoads)

35. Subterranean Homesick Blues

36. California Dreaming

37. Rambling' Man

38. Ohio

39. West Side Rumble

40. West Side Cool (2:30)

42. Beat it

43. And so it goes--Joel

44. And so it goes--King's Singers

NOTE: 45-57 in the American Classical music secion below are also for consideration for this online assignment

__________

American Classical Music

Antonín Dvořák, in full Antonín Leopold Dvořák (born September 8, 1841, Nelahozeves, Bohemia, Austrian Empire [now in Czech Republic]—died May 1, 1904, Prague), first Bohemian composer to achieve worldwide recognition, noted for turning folk material into the language of 19th-century Romantic music.

LifeDvořák was born, the first of nine children, in Nelahozeves, a Bohemian (now Czech) village on the Vltava River north of Prague. He came to know music early, in and about his father’s inn, and became an accomplished violinist as a youngster, contributing to the amateur music-making that accompanied the dances of the local couples. Though it was assumed that he would become a butcher and innkeeper like his father (who also played the zither), the boy had an unmistakable talent for music that was recognized and encouraged. When he was about 12 years old, he moved to Zlonice to live with an aunt and uncle and began studying harmony, piano, and organ. He wrote his earliest works, polkas, during the three years he spent in Zlonice. In 1857 a perceptive music teacher, understanding that young Antonín had gone beyond his own modest abilities to teach him, persuaded his father to enroll him at the Institute for Church Music in Prague. There Dvořák completed a two-year course and played the viola in various inns and with theatre bands, augmenting his small salary with a few private pupils.

The 1860s were trying years for Dvořák, who was hard-pressed for both time and the means, even paper and a piano, to compose. In later years he said he had little recollection of what he wrote in those days, but about 1864 two symphonies, an opera, chamber music, and numerous songs lay unheard in his desk. The varied works of this period show that his earlier leanings toward the music of Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert were becoming increasingly tinged with the influence of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt.

Among the students Dvořák tutored throughout the 1860s were the sisters Josefina and Anna Čermáková. The musician fell in love with the elder sister, Josefina, but she did not reciprocate his feelings. The anguish of his unrequited love is said to be expressed in Cypresses (1865), a number of songs set to texts by Gustav Pfleger-Moravský. In November 1873 he married the younger sister, Anna, a pianist and singer. The first few years of the Dvořáks’ marriage were challenged by financial insecurity and marked by tragedy. Anna had given birth to three children by 1876 but by 1877 had buried all of them. In 1878, however, she gave birth to the first of the six healthy children the couple would raise together. The Dvořáks maintained a close relationship with Josefina and the man she eventually married, Count Václav Kounic. After several years of regular visits, they bought a summer house in the small village of Vysoká, where Josefina and the count had settled, and spent every summer there from that point onward. Dvořák composed some of his best-known works there.

In 1875 Dvořák was awarded a state grant by the Austrian government, and this award brought him into contact with Johannes Brahms, with whom he formed a close and fruitful friendship. Brahms not only gave him valuable technical advice but also found him an influential publisher in Fritz Simrock, and it was with his firm’s publication of the Moravian Duets (composed 1876) for soprano and contralto and the Slavonic Dances (1878) for piano duet that Dvořák first attracted worldwide attention to himself and to his country’s music. The admiration of the leading critics, instrumentalists, and conductors of the day continued to spread his fame abroad, which led naturally to even greater triumphs in his own country. In 1884 he made the first of 10 visits to England, where the success of his works, especially his choralworks, was a source of constant pride to him, although only the Stabat Mater (1877) and Te Deum (1892) continue to hold a position among the finer works of their kind. In 1890 he enjoyed a personal triumph in Moscow, where two concerts were arranged for him by his friend Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The following year he was made an honorary doctor of music of the University of Cambridge.

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

Vegetable Variety: Fact or Fiction?Dvořák accepted the post of director of the newly established National Conservatory of Music in New York in 1892, and, during his years in the United States, he traveled as far west as Iowa. Though he found much to interest and stimulate him in the New World environment, he soon came to miss his own country, and he returned to Bohemia in 1895. The final years of his life saw the composition of several string quartets and symphonic poems and his last three operas.

From the Encyclopedia Britannica

45. "From the New World" Symphony No. 9 (4th mvt.)

LifeDvořák was born, the first of nine children, in Nelahozeves, a Bohemian (now Czech) village on the Vltava River north of Prague. He came to know music early, in and about his father’s inn, and became an accomplished violinist as a youngster, contributing to the amateur music-making that accompanied the dances of the local couples. Though it was assumed that he would become a butcher and innkeeper like his father (who also played the zither), the boy had an unmistakable talent for music that was recognized and encouraged. When he was about 12 years old, he moved to Zlonice to live with an aunt and uncle and began studying harmony, piano, and organ. He wrote his earliest works, polkas, during the three years he spent in Zlonice. In 1857 a perceptive music teacher, understanding that young Antonín had gone beyond his own modest abilities to teach him, persuaded his father to enroll him at the Institute for Church Music in Prague. There Dvořák completed a two-year course and played the viola in various inns and with theatre bands, augmenting his small salary with a few private pupils.

The 1860s were trying years for Dvořák, who was hard-pressed for both time and the means, even paper and a piano, to compose. In later years he said he had little recollection of what he wrote in those days, but about 1864 two symphonies, an opera, chamber music, and numerous songs lay unheard in his desk. The varied works of this period show that his earlier leanings toward the music of Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert were becoming increasingly tinged with the influence of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt.

Among the students Dvořák tutored throughout the 1860s were the sisters Josefina and Anna Čermáková. The musician fell in love with the elder sister, Josefina, but she did not reciprocate his feelings. The anguish of his unrequited love is said to be expressed in Cypresses (1865), a number of songs set to texts by Gustav Pfleger-Moravský. In November 1873 he married the younger sister, Anna, a pianist and singer. The first few years of the Dvořáks’ marriage were challenged by financial insecurity and marked by tragedy. Anna had given birth to three children by 1876 but by 1877 had buried all of them. In 1878, however, she gave birth to the first of the six healthy children the couple would raise together. The Dvořáks maintained a close relationship with Josefina and the man she eventually married, Count Václav Kounic. After several years of regular visits, they bought a summer house in the small village of Vysoká, where Josefina and the count had settled, and spent every summer there from that point onward. Dvořák composed some of his best-known works there.

In 1875 Dvořák was awarded a state grant by the Austrian government, and this award brought him into contact with Johannes Brahms, with whom he formed a close and fruitful friendship. Brahms not only gave him valuable technical advice but also found him an influential publisher in Fritz Simrock, and it was with his firm’s publication of the Moravian Duets (composed 1876) for soprano and contralto and the Slavonic Dances (1878) for piano duet that Dvořák first attracted worldwide attention to himself and to his country’s music. The admiration of the leading critics, instrumentalists, and conductors of the day continued to spread his fame abroad, which led naturally to even greater triumphs in his own country. In 1884 he made the first of 10 visits to England, where the success of his works, especially his choralworks, was a source of constant pride to him, although only the Stabat Mater (1877) and Te Deum (1892) continue to hold a position among the finer works of their kind. In 1890 he enjoyed a personal triumph in Moscow, where two concerts were arranged for him by his friend Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The following year he was made an honorary doctor of music of the University of Cambridge.

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

Vegetable Variety: Fact or Fiction?Dvořák accepted the post of director of the newly established National Conservatory of Music in New York in 1892, and, during his years in the United States, he traveled as far west as Iowa. Though he found much to interest and stimulate him in the New World environment, he soon came to miss his own country, and he returned to Bohemia in 1895. The final years of his life saw the composition of several string quartets and symphonic poems and his last three operas.

From the Encyclopedia Britannica

45. "From the New World" Symphony No. 9 (4th mvt.)

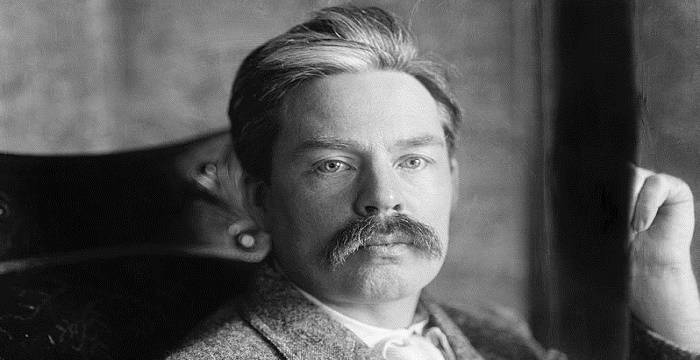

Ferde Grofé,

byname of Ferdinand Rudolph von Grofé (born March 27, 1892, New York, N.Y., U.S.—died April 3, 1972, Santa Monica, Calif.), American composer and arranger known for his orchestral works as well as for his pioneering role in establishing the sound of big band dance music.

Grofé was reared in Los Angeles, where his father was an actor and singer and his mother taught music and played cello. Although his parents had wanted him to study law, he left college to focus on music. By 1908 he was performing as a violinist, violist, and pianist. He played viola with the Los Angeles Symphony from 1909 through 1919; concurrently, he worked with drummer Art Hickman’s orchestra starting in 1914. For Hickman, Grofé conceived arrangements that divided the ensemble into separate brass and reed sections, writing countermelodies to the main melody and using different musical settings for each return of the chorus to a piece. His innovations were an important early step in the development of big band jazz and dance music.

In 1917 Grofé joined the orchestra of Paul Whiteman, serving briefly as band pianist and continuing as one of Whiteman’s main arrangers until 1932. Among his arrangements were the hits “Whispering,” “Japanese Sandman,” and “Three o’Clock in the Morning.” More significantly, he orchestrated George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue for its debut performance with the Whiteman orchestra in 1924. Grofé helped Whiteman realize the goal of combining the rhythms of jazz and dance music with elements of classical music.

Grofé wrote several original works during his tenure with Whiteman, including Mississippi Suite (1925) and his best-known composition, Grand Canyon Suite (1931), from which the movement “On the Trail” became a jazz standard. After leaving Whiteman, Grofé formed his own orchestra, which often performed for radio. He continued to compose ambitious, picturesque works, including 6 Pictures of Hollywood (1937), Hudson River Suite (1955), Death Valley Suite (1957), and World’s Fair Suite (1964). Grofé also taught at the Juilliard School of Music (1939–42), scored ballets, and wrote the music for several Hollywood films, including Minstrel Man (1944), Time out of Mind (1947), and The Return of Jesse James(1950).

WRITTEN BY:

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica

See Article History

46. "On the Trail" from Grand Canyon Suite (Bernstein conducts the NY Phil)

47. "Cloudburst" from Grand Canyon Suite (Bernstein/NYP)

byname of Ferdinand Rudolph von Grofé (born March 27, 1892, New York, N.Y., U.S.—died April 3, 1972, Santa Monica, Calif.), American composer and arranger known for his orchestral works as well as for his pioneering role in establishing the sound of big band dance music.

Grofé was reared in Los Angeles, where his father was an actor and singer and his mother taught music and played cello. Although his parents had wanted him to study law, he left college to focus on music. By 1908 he was performing as a violinist, violist, and pianist. He played viola with the Los Angeles Symphony from 1909 through 1919; concurrently, he worked with drummer Art Hickman’s orchestra starting in 1914. For Hickman, Grofé conceived arrangements that divided the ensemble into separate brass and reed sections, writing countermelodies to the main melody and using different musical settings for each return of the chorus to a piece. His innovations were an important early step in the development of big band jazz and dance music.

In 1917 Grofé joined the orchestra of Paul Whiteman, serving briefly as band pianist and continuing as one of Whiteman’s main arrangers until 1932. Among his arrangements were the hits “Whispering,” “Japanese Sandman,” and “Three o’Clock in the Morning.” More significantly, he orchestrated George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue for its debut performance with the Whiteman orchestra in 1924. Grofé helped Whiteman realize the goal of combining the rhythms of jazz and dance music with elements of classical music.

Grofé wrote several original works during his tenure with Whiteman, including Mississippi Suite (1925) and his best-known composition, Grand Canyon Suite (1931), from which the movement “On the Trail” became a jazz standard. After leaving Whiteman, Grofé formed his own orchestra, which often performed for radio. He continued to compose ambitious, picturesque works, including 6 Pictures of Hollywood (1937), Hudson River Suite (1955), Death Valley Suite (1957), and World’s Fair Suite (1964). Grofé also taught at the Juilliard School of Music (1939–42), scored ballets, and wrote the music for several Hollywood films, including Minstrel Man (1944), Time out of Mind (1947), and The Return of Jesse James(1950).

WRITTEN BY:

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica

See Article History

46. "On the Trail" from Grand Canyon Suite (Bernstein conducts the NY Phil)

47. "Cloudburst" from Grand Canyon Suite (Bernstein/NYP)

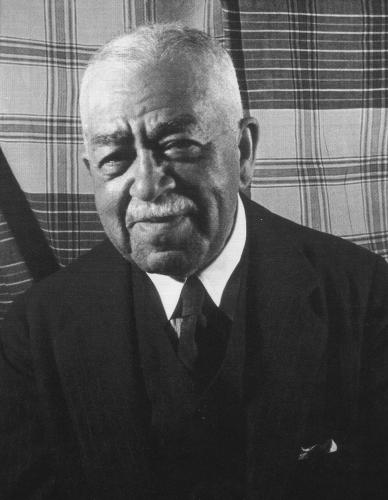

H. T. Burleigh (1866-1949)

[Harry Thacker Burleigh, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right], 1927. Prints and Photographs Reading Room, Library of Congress.Although his name is relatively unknown, Harry Thacker Burleigh (named Henry after his father) played a significant role in the development of American art song, having composed over two hundred works in the genre. He was the first African-American composer acclaimed for his concert songs as well as for his adaptations of African-American spirituals. In addition, Burleigh was an accomplished baritone, a meticulous editor, and a charter member of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP).

Born in Erie, Pennsylvania, on 2 December 1866, Burleigh received his first music training from his mother. After discovering Burleigh's musical talent, Elizabeth Russell, a bank messenger who was his mother's employer, gave the youth a job as a doorman at the musicales she hosted in her home. This afforded Burleigh the opportunity to hear guest performers such as Teresa Carreño and Italo Campanini. Although he had no formal training, his talent as a singer led to employment as a soloist in several Erie churches and synagogues. In 1892, at the age of twenty-six, Burleigh received a scholarship (with some intervention in his behalf from Mrs. Frances MacDowell, mother of famed American composer Edward MacDowell) to the National Conservatory of Music in New York where he studied with Christian Fritsch, Rubin Goldmark, John White, and Max Spicker.

The years Burleigh spent at the Conservatory greatly influenced his career, mostly due to his association and friendship with Antonín Dvorák, the Conservatory's director. After spending countless hours recalling and performing the African-American spirituals and plantation songs he had learned from his maternal grandfather for Dvorák, Burleigh was encouraged by the elder composer to preserve these melodies in his own compositions. In turn, Dvorák's use of the spirituals "Goin' Home" and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" in his Symphony no. 9 in E minor ("From the New World") was probably influenced by his sessions with Burleigh. In addition, Burleigh served as copyist for Dvorák, a task that prepared him for his future responsibilities as a music editor.

In 1894, Burleigh auditioned for the post of soloist at St. George's Episcopal Church of New York. To the consternation of the congregation, which objected because Burleigh was black, he was given the position. However, through his talent and dedication (he held the appointment for over fifty years, missing only one performance during his tenure), Burleigh won the hearts and the respect of the entire church community.

Personally and professionally, the next several years were productive ones for Burleigh. In 1898, he married poet Louise Alston; a son, Alston, was born the following year. That same year, G. Schirmer published his first three songs. In 1900, Burleigh was the first African-American chosen as soloist at Temple Emanu-El, a New York synagogue, and by 1911 he was working as an editor for music publisher G. Ricordi. His success was enhanced through the publication of several of his compositions, including "Ethiopia Saluting the Colors" (1915), a collection entitled Jubilee Songs of the USA (1916), and his arrangement of "Deep River" (1917), for which he is best remembered.

The widespread success of his setting of Deep River(1917) inspired the publication of nearly a dozen more spirituals the same year. The settings appeared in multiple versions upon publication, including vocal solos in a variety of keys and choral arrangements prepared by Burleigh and others for mixed chorus, men's chorus, and women's chorus. As his spiritual arrangements become increasingly popular with concert soloists, a tradition of concluding concerts with a set of spirituals was established.

Burleigh's achievement in solo vocal writing is best represented by his original song cycles, Saracen Songs (1914), Passionale (1915), and Five Songs of Laurence Hope (1915), considered by many to be his finest work. His instrumental output includes the unpublished Six Plantation Melodies for violin and piano (1901), From the Southland for piano (1910), and Southland Sketches for violin and piano (1916).

Burleigh died at age 82 on 12 September 1949. Over 2,000 mourners attended the funeral of the man who had successfully combined the melodies of his own heritage with those of serious art music. Burleigh's compositions and arrangements of African-American spirituals transported the music of the "colored folk" from their plantation and minstrel settings onto the concert stage, where they have been enjoyed and appreciated by people of all races.

48. "My Lord What a Morning" (Choral Arts)

49. "Deep River" (Stokowski/Luboff) (arr)

[Harry Thacker Burleigh, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right], 1927. Prints and Photographs Reading Room, Library of Congress.Although his name is relatively unknown, Harry Thacker Burleigh (named Henry after his father) played a significant role in the development of American art song, having composed over two hundred works in the genre. He was the first African-American composer acclaimed for his concert songs as well as for his adaptations of African-American spirituals. In addition, Burleigh was an accomplished baritone, a meticulous editor, and a charter member of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP).

Born in Erie, Pennsylvania, on 2 December 1866, Burleigh received his first music training from his mother. After discovering Burleigh's musical talent, Elizabeth Russell, a bank messenger who was his mother's employer, gave the youth a job as a doorman at the musicales she hosted in her home. This afforded Burleigh the opportunity to hear guest performers such as Teresa Carreño and Italo Campanini. Although he had no formal training, his talent as a singer led to employment as a soloist in several Erie churches and synagogues. In 1892, at the age of twenty-six, Burleigh received a scholarship (with some intervention in his behalf from Mrs. Frances MacDowell, mother of famed American composer Edward MacDowell) to the National Conservatory of Music in New York where he studied with Christian Fritsch, Rubin Goldmark, John White, and Max Spicker.

The years Burleigh spent at the Conservatory greatly influenced his career, mostly due to his association and friendship with Antonín Dvorák, the Conservatory's director. After spending countless hours recalling and performing the African-American spirituals and plantation songs he had learned from his maternal grandfather for Dvorák, Burleigh was encouraged by the elder composer to preserve these melodies in his own compositions. In turn, Dvorák's use of the spirituals "Goin' Home" and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" in his Symphony no. 9 in E minor ("From the New World") was probably influenced by his sessions with Burleigh. In addition, Burleigh served as copyist for Dvorák, a task that prepared him for his future responsibilities as a music editor.

In 1894, Burleigh auditioned for the post of soloist at St. George's Episcopal Church of New York. To the consternation of the congregation, which objected because Burleigh was black, he was given the position. However, through his talent and dedication (he held the appointment for over fifty years, missing only one performance during his tenure), Burleigh won the hearts and the respect of the entire church community.

Personally and professionally, the next several years were productive ones for Burleigh. In 1898, he married poet Louise Alston; a son, Alston, was born the following year. That same year, G. Schirmer published his first three songs. In 1900, Burleigh was the first African-American chosen as soloist at Temple Emanu-El, a New York synagogue, and by 1911 he was working as an editor for music publisher G. Ricordi. His success was enhanced through the publication of several of his compositions, including "Ethiopia Saluting the Colors" (1915), a collection entitled Jubilee Songs of the USA (1916), and his arrangement of "Deep River" (1917), for which he is best remembered.

The widespread success of his setting of Deep River(1917) inspired the publication of nearly a dozen more spirituals the same year. The settings appeared in multiple versions upon publication, including vocal solos in a variety of keys and choral arrangements prepared by Burleigh and others for mixed chorus, men's chorus, and women's chorus. As his spiritual arrangements become increasingly popular with concert soloists, a tradition of concluding concerts with a set of spirituals was established.

Burleigh's achievement in solo vocal writing is best represented by his original song cycles, Saracen Songs (1914), Passionale (1915), and Five Songs of Laurence Hope (1915), considered by many to be his finest work. His instrumental output includes the unpublished Six Plantation Melodies for violin and piano (1901), From the Southland for piano (1910), and Southland Sketches for violin and piano (1916).

Burleigh died at age 82 on 12 September 1949. Over 2,000 mourners attended the funeral of the man who had successfully combined the melodies of his own heritage with those of serious art music. Burleigh's compositions and arrangements of African-American spirituals transported the music of the "colored folk" from their plantation and minstrel settings onto the concert stage, where they have been enjoyed and appreciated by people of all races.

48. "My Lord What a Morning" (Choral Arts)

49. "Deep River" (Stokowski/Luboff) (arr)

PHILLIP GLASS

biographyThrough his operas, his symphonies, his compositions for his own ensemble, and his wide-ranging collaborations with artists ranging from Twyla Tharp to Allen Ginsberg, Woody Allen to David Bowie, Philip Glass has had an extraordinary and unprecedented impact upon the musical and intellectual life of his times.

The operas – “Einstein on the Beach,” “Satyagraha,” “Akhnaten,” and “The Voyage,” among many others – play throughout the world’s leading houses, and rarely to an empty seat. Glass has written music for experimental theater and for Academy Award-winning motion pictures such as “The Hours” and Martin Scorsese’s “Kundun,” while “Koyaanisqatsi,” his initial filmic landscape with Godfrey Reggio and the Philip Glass Ensemble, may be the most radical and influential mating of sound and vision since “Fantasia.” His associations, personal and professional, with leading rock, pop and world music artists date back to the 1960s, including the beginning of his collaborative relationship with artist Robert Wilson. Indeed, Glass is the first composer to win a wide, multi-generational audience in the opera house, the concert hall, the dance world, in film and in popular music – simultaneously.

He was born in 1937 and grew up in Baltimore. He studied at the University of Chicago, the Juilliard School and in Aspen with Darius Milhaud. Finding himself dissatisfied with much of what then passed for modern music, he moved to Europe, where he studied with the legendary pedagogue Nadia Boulanger (who also taught Aaron Copland , Virgil Thomson and Quincy Jones) and worked closely with the sitar virtuoso and composer Ravi Shankar. He returned to New York in 1967 and formed the Philip Glass Ensemble – seven musicians playing keyboards and a variety of woodwinds, amplified and fed through a mixer.

The new musical style that Glass was evolving was eventually dubbed “minimalism.” Glass himself never liked the term and preferred to speak of himself as a composer of “music with repetitive structures.” Much of his early work was based on the extended reiteration of brief, elegant melodic fragments that wove in and out of an aural tapestry. Or, to put it another way, it immersed a listener in a sort of sonic weather that twists, turns, surrounds, develops.

There has been nothing “minimalist” about his output. In the past 25 years, Glass has composed more than twenty operas, large and small; ten symphonies (with others already on the way); two piano concertos and concertos for violin, piano, timpani, and saxophone quartet and orchestra; soundtracks to films ranging from new scores for the stylized classics of Jean Cocteau to Errol Morris’s documentary about former defense secretary Robert McNamara; string quartets; a growing body of work for solo piano and organ. He has collaborated with Paul Simon, Linda Ronstadt, Yo-Yo Ma, and Doris Lessing, among many others. He presents lectures, workshops, and solo keyboard performances around the world, and continues to appear regularly with the Philip Glass Ensemble.

bio from phillipglass.com

50. "The Poet Acts"

52. "Morning Passages"

biographyThrough his operas, his symphonies, his compositions for his own ensemble, and his wide-ranging collaborations with artists ranging from Twyla Tharp to Allen Ginsberg, Woody Allen to David Bowie, Philip Glass has had an extraordinary and unprecedented impact upon the musical and intellectual life of his times.

The operas – “Einstein on the Beach,” “Satyagraha,” “Akhnaten,” and “The Voyage,” among many others – play throughout the world’s leading houses, and rarely to an empty seat. Glass has written music for experimental theater and for Academy Award-winning motion pictures such as “The Hours” and Martin Scorsese’s “Kundun,” while “Koyaanisqatsi,” his initial filmic landscape with Godfrey Reggio and the Philip Glass Ensemble, may be the most radical and influential mating of sound and vision since “Fantasia.” His associations, personal and professional, with leading rock, pop and world music artists date back to the 1960s, including the beginning of his collaborative relationship with artist Robert Wilson. Indeed, Glass is the first composer to win a wide, multi-generational audience in the opera house, the concert hall, the dance world, in film and in popular music – simultaneously.

He was born in 1937 and grew up in Baltimore. He studied at the University of Chicago, the Juilliard School and in Aspen with Darius Milhaud. Finding himself dissatisfied with much of what then passed for modern music, he moved to Europe, where he studied with the legendary pedagogue Nadia Boulanger (who also taught Aaron Copland , Virgil Thomson and Quincy Jones) and worked closely with the sitar virtuoso and composer Ravi Shankar. He returned to New York in 1967 and formed the Philip Glass Ensemble – seven musicians playing keyboards and a variety of woodwinds, amplified and fed through a mixer.

The new musical style that Glass was evolving was eventually dubbed “minimalism.” Glass himself never liked the term and preferred to speak of himself as a composer of “music with repetitive structures.” Much of his early work was based on the extended reiteration of brief, elegant melodic fragments that wove in and out of an aural tapestry. Or, to put it another way, it immersed a listener in a sort of sonic weather that twists, turns, surrounds, develops.

There has been nothing “minimalist” about his output. In the past 25 years, Glass has composed more than twenty operas, large and small; ten symphonies (with others already on the way); two piano concertos and concertos for violin, piano, timpani, and saxophone quartet and orchestra; soundtracks to films ranging from new scores for the stylized classics of Jean Cocteau to Errol Morris’s documentary about former defense secretary Robert McNamara; string quartets; a growing body of work for solo piano and organ. He has collaborated with Paul Simon, Linda Ronstadt, Yo-Yo Ma, and Doris Lessing, among many others. He presents lectures, workshops, and solo keyboard performances around the world, and continues to appear regularly with the Philip Glass Ensemble.

bio from phillipglass.com

50. "The Poet Acts"

52. "Morning Passages"

Charles Ives, in full Charles Edward Ives (born October 20, 1874, Danbury, Connecticut, U.S.—died May 19, 1954, New York City), significant American composer who is known for a number of innovations that anticipated most of the later musical developments of the 20th century.

Ives received his earliest musical instruction from his father, who was a bandleader, music teacher, and acoustician who experimented with the sound of quarter tones. At 12 Charles played organ in a local church, and two years later his first composition was played by the town band. In 1893 or 1894 he composed “Song for the Harvest Season,” in which the four parts—for voice, trumpet, violin, and organ—were in different keys. That year he began studying at Yale University under Horatio Parker, then the foremost academic composer in the United States. His unconventionality disconcerted Parker, for whom Ives eventually turned out a series of “correct” compositions.

After graduation in 1898, Ives became an insurance clerk and part-time organist in New York City. In 1907 he founded the highly successful insurance partnership of Ives & Myrick, which he headed from 1916 to 1930. He devised the insurance concept of estate planning and considered his years in business a valuable human experience that contributed to the substance of his music. Nearly all his works were written before 1915; many lay unpublished until his death. Chronic diabetes and a hand tremor eventually forced him to give up composing and to retire from business. His music became widely known only in the last years of his life. In 1947 he received the Pulitzer Prize for his Third Symphony (The Camp Meeting; composed 1904–11). His Second Symphony (1897–1902) was first performed in its entirety 50 years after its composition.

from the Charles Ives website

53. "Putnam's Camp" from Three Places in New England

Ives received his earliest musical instruction from his father, who was a bandleader, music teacher, and acoustician who experimented with the sound of quarter tones. At 12 Charles played organ in a local church, and two years later his first composition was played by the town band. In 1893 or 1894 he composed “Song for the Harvest Season,” in which the four parts—for voice, trumpet, violin, and organ—were in different keys. That year he began studying at Yale University under Horatio Parker, then the foremost academic composer in the United States. His unconventionality disconcerted Parker, for whom Ives eventually turned out a series of “correct” compositions.

After graduation in 1898, Ives became an insurance clerk and part-time organist in New York City. In 1907 he founded the highly successful insurance partnership of Ives & Myrick, which he headed from 1916 to 1930. He devised the insurance concept of estate planning and considered his years in business a valuable human experience that contributed to the substance of his music. Nearly all his works were written before 1915; many lay unpublished until his death. Chronic diabetes and a hand tremor eventually forced him to give up composing and to retire from business. His music became widely known only in the last years of his life. In 1947 he received the Pulitzer Prize for his Third Symphony (The Camp Meeting; composed 1904–11). His Second Symphony (1897–1902) was first performed in its entirety 50 years after its composition.

from the Charles Ives website

53. "Putnam's Camp" from Three Places in New England

Edward McDowell was one of the most celebrated American composers in the nineteenth century. His compositions won the approval of music critics, both in Europe and the United States, as well as of his contemporaries, including composers such as Franz Liszt and Joachim Raff. MacDowell's early works bear the influence of his training in Germany, reflecting European styles and cultures. Nearly all of his compositions feature descriptive titles, a trend representative of Romantic music. He was among the first seven Americans honored by membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1904).

In 1876, at the age of fifteen, MacDowell, accompanied by his mother, traveled to France to enroll in the Paris Conservatoire. He earned one of the conservatoire's scholarships awarded to foreign students and gained admission to Antoine François Marmontel's studio. Marmontel was one of the most sought-after piano teachers of the time, and he accepted only thirteen students, including MacDowell, out of 230 applicants. After only two years, MacDowell grew dissatisfied with the instruction at the conservatoire and moved to Germany to continue his education.

In the fall of 1879, MacDowell entered the Frankfurt Conservatory, where he studied piano with Carl Heymann and composition with Joachim Raff. It was during this time that MacDowell became acquainted with Franz Liszt. Upon visiting Raff's class in early 1880, Liszt heard MacDowell play the piano part of Robert Schumann's Quintet, op. 44 (Schumann's widow, Clara, was also present at that performance). The following year, MacDowell visited Liszt in Weimar and played his own Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 15, for the maestro. On Liszt's recommendation, MacDowell's First Modern Suite, op. 10, was performed on 11 July 1882 at the Allgemeine deutsche Musikverein; Liszt also encouraged the prestigious Leipzig firm of Breitkopf & Härtel to publish the work.

Financial difficulties forced the MacDowells to return to America in 1888, and for nearly ten years they resided in Boston. Among the compositions penned by MacDowell during this period was his Indian Suite, op. 48 (1896), for orchestra, one of his most famous works. In 1896 the MacDowells purchased land in New Hampshire, and in a cabin built on this property, Edward composed his Woodland Sketches, op. 51 (1896), for piano. The natural surroundings of this New Hampshire retreat would ultimately inspire generations of composers, for it was in this location in 1907 that the MacDowell Colony was established. The colony, a sanctuary for composers, painters, authors, and sculptors, continues to sponsor and support artists to this day.

MacDowell joined the faculty of Columbia University in 1896. As the sole music professor at the university for nearly two years, MacDowell also served as the department's administrator. In addition to teaching, he directed the Mendelssohn Glee Club (New York). He also started an all-male chorus at Columbia University in order to raise artistic standards of college glee clubs and music societies.

54. "To A Wild Rose"

In 1876, at the age of fifteen, MacDowell, accompanied by his mother, traveled to France to enroll in the Paris Conservatoire. He earned one of the conservatoire's scholarships awarded to foreign students and gained admission to Antoine François Marmontel's studio. Marmontel was one of the most sought-after piano teachers of the time, and he accepted only thirteen students, including MacDowell, out of 230 applicants. After only two years, MacDowell grew dissatisfied with the instruction at the conservatoire and moved to Germany to continue his education.

In the fall of 1879, MacDowell entered the Frankfurt Conservatory, where he studied piano with Carl Heymann and composition with Joachim Raff. It was during this time that MacDowell became acquainted with Franz Liszt. Upon visiting Raff's class in early 1880, Liszt heard MacDowell play the piano part of Robert Schumann's Quintet, op. 44 (Schumann's widow, Clara, was also present at that performance). The following year, MacDowell visited Liszt in Weimar and played his own Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 15, for the maestro. On Liszt's recommendation, MacDowell's First Modern Suite, op. 10, was performed on 11 July 1882 at the Allgemeine deutsche Musikverein; Liszt also encouraged the prestigious Leipzig firm of Breitkopf & Härtel to publish the work.

Financial difficulties forced the MacDowells to return to America in 1888, and for nearly ten years they resided in Boston. Among the compositions penned by MacDowell during this period was his Indian Suite, op. 48 (1896), for orchestra, one of his most famous works. In 1896 the MacDowells purchased land in New Hampshire, and in a cabin built on this property, Edward composed his Woodland Sketches, op. 51 (1896), for piano. The natural surroundings of this New Hampshire retreat would ultimately inspire generations of composers, for it was in this location in 1907 that the MacDowell Colony was established. The colony, a sanctuary for composers, painters, authors, and sculptors, continues to sponsor and support artists to this day.

MacDowell joined the faculty of Columbia University in 1896. As the sole music professor at the university for nearly two years, MacDowell also served as the department's administrator. In addition to teaching, he directed the Mendelssohn Glee Club (New York). He also started an all-male chorus at Columbia University in order to raise artistic standards of college glee clubs and music societies.

54. "To A Wild Rose"

Aaron Copland was one of the most respected American classical composers of the twentieth century. By incorporating popular forms of American music such as jazz and folk into his compositions, he created pieces both exceptional and innovative. As a spokesman for the advancement of indigenous American music, Copland made great strides in liberating it from European influence. Today, ten years after his death, Copland’s life and work continue to inspire many of America’s young composers.

Copland was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 14, 1900. The child of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania, he first learned to play the piano from his older sister. At the age of sixteen he went to Manhattan to study with Rubin Goldmark, a respected private music instructor who taught Copland the fundamentals of counterpoint and composition. During these early years he immersed himself in contemporary classical music by attending performances at the New York Symphony and Brooklyn Academy of Music. He found, however, that like many other young musicians, he was attracted to the classical history and musicians of Europe. So, at the age of twenty, he left New York for the Summer School of Music for American Students at Fountainebleau, France.

In France, Copland found a musical community unlike any he had known. It was at this time that he sold his first composition to Durand and Sons, the most respected music publisher in France. While in Europe Copeland met many of the important artists of the time, including the famous composer Serge Koussevitsky. Koussevitsky requested that Copland write a piece for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The piece, “Symphony for Organ and Orchestra” (1925) was Copland’s entry into the life of professional American music. He followed this with “Music for the Theater” (1925) and “Piano Concerto” (1926), both of which relied heavily on the jazz idioms of the time. For Copland, jazz was the first genuinely American major musical movement. From jazz he hoped to draw the inspiration for a new type of symphonic music, one that could distinguish itself from the music of Europe.

In the late 1920s Copland’s attention turned to popular music of other countries. He had moved away from his interest in jazz and began to concern himself with expanding the audience for American classical music. He believed that classical music could eventually be as popular as jazz in America or folk music in Mexico. He worked toward this goal with both his music and a firm commitment to organizing and producing. He was an active member of many organizations, including both the American Composers’ Alliance and the League of Composers. Along with his friend Roger Sessions, he began the Copland-Sessions concerts, dedicated to presenting the works of young composers. It was around this same time that his plans for an American music festival (similar to ones in Europe) materialized as the Yaddo Festival of American Music (1932). By the mid-’30s Copland had become not only one of the most popular composers in the country, but a leader of the community of American classical musicians.

It was in 1935 with “El Salón México” that Copland began his most productive and popular years. The piece presented a new sound that had its roots in Mexican folk music. Copland believed that through this music, he could find his way to a more popular symphonic music. In his search for the widest audience, Copland began composing for the movies and ballet. Among his most popular compositions for film are those for “Of Mice and Men” (1939), “Our Town ” (1940), and “The Heiress” (1949), which won him an Academy Award for best score. He composed scores for a number of ballets, including two of the most popular of the time: “Agnes DeMille’s Rodeo” (1942) and Martha Graham‘s “Appalachian Spring” (1944), for which he won the Pulitzer Prize. Both ballets presented views of American country life that corresponded to the folk traditions Copland was interested in. Probably the most important and successful composition from this time was his patriotic “A Lincoln Portrait” (1942). The piece for voice and orchestra presents quotes from Lincoln’s writings narrated over Copland’s musical composition.

Throughout the ’50s, Copland slowed his work as a composer, and began to try his hand at conducting. He began to tour with his own work as well as the works of other great American musicians. Conducting was a synthesis of the work he had done as a composer and as an organizer. Over the next twenty years he traveled throughout the world, conducting live performances and creating an important collection of recorded work. By the early ’70s, Copland had, with few exceptions, completely stopped writing original music. Most of his time was spent conducting and reworking older compositions. In 1983 Copland conducted his last symphony. His generous work as a teacher at Tanglewood, Harvard, and the New School for Social Research gained him a following of devoted musicians. As a scholar, he wrote more than sixty articles and essays on music, as well as five books. He traveled the world in an attempt to elevate the status of American music abroad, and to increase its popularity at home. Through these various commitments to music and to his country, Aaron Copland became one of the most important figures in twentieth-century American music. On December 2, 1990, Aaron Copland died in North Tarrytown, New York.

55. "Simple Gifts" from Appalachian Spring (Leonard Bernstein, conductor)

56. "Fanfare For The Common Man" (Eugene Goossens, Cincinnati Symphony)

Copland was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 14, 1900. The child of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania, he first learned to play the piano from his older sister. At the age of sixteen he went to Manhattan to study with Rubin Goldmark, a respected private music instructor who taught Copland the fundamentals of counterpoint and composition. During these early years he immersed himself in contemporary classical music by attending performances at the New York Symphony and Brooklyn Academy of Music. He found, however, that like many other young musicians, he was attracted to the classical history and musicians of Europe. So, at the age of twenty, he left New York for the Summer School of Music for American Students at Fountainebleau, France.

In France, Copland found a musical community unlike any he had known. It was at this time that he sold his first composition to Durand and Sons, the most respected music publisher in France. While in Europe Copeland met many of the important artists of the time, including the famous composer Serge Koussevitsky. Koussevitsky requested that Copland write a piece for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The piece, “Symphony for Organ and Orchestra” (1925) was Copland’s entry into the life of professional American music. He followed this with “Music for the Theater” (1925) and “Piano Concerto” (1926), both of which relied heavily on the jazz idioms of the time. For Copland, jazz was the first genuinely American major musical movement. From jazz he hoped to draw the inspiration for a new type of symphonic music, one that could distinguish itself from the music of Europe.

In the late 1920s Copland’s attention turned to popular music of other countries. He had moved away from his interest in jazz and began to concern himself with expanding the audience for American classical music. He believed that classical music could eventually be as popular as jazz in America or folk music in Mexico. He worked toward this goal with both his music and a firm commitment to organizing and producing. He was an active member of many organizations, including both the American Composers’ Alliance and the League of Composers. Along with his friend Roger Sessions, he began the Copland-Sessions concerts, dedicated to presenting the works of young composers. It was around this same time that his plans for an American music festival (similar to ones in Europe) materialized as the Yaddo Festival of American Music (1932). By the mid-’30s Copland had become not only one of the most popular composers in the country, but a leader of the community of American classical musicians.

It was in 1935 with “El Salón México” that Copland began his most productive and popular years. The piece presented a new sound that had its roots in Mexican folk music. Copland believed that through this music, he could find his way to a more popular symphonic music. In his search for the widest audience, Copland began composing for the movies and ballet. Among his most popular compositions for film are those for “Of Mice and Men” (1939), “Our Town ” (1940), and “The Heiress” (1949), which won him an Academy Award for best score. He composed scores for a number of ballets, including two of the most popular of the time: “Agnes DeMille’s Rodeo” (1942) and Martha Graham‘s “Appalachian Spring” (1944), for which he won the Pulitzer Prize. Both ballets presented views of American country life that corresponded to the folk traditions Copland was interested in. Probably the most important and successful composition from this time was his patriotic “A Lincoln Portrait” (1942). The piece for voice and orchestra presents quotes from Lincoln’s writings narrated over Copland’s musical composition.

Throughout the ’50s, Copland slowed his work as a composer, and began to try his hand at conducting. He began to tour with his own work as well as the works of other great American musicians. Conducting was a synthesis of the work he had done as a composer and as an organizer. Over the next twenty years he traveled throughout the world, conducting live performances and creating an important collection of recorded work. By the early ’70s, Copland had, with few exceptions, completely stopped writing original music. Most of his time was spent conducting and reworking older compositions. In 1983 Copland conducted his last symphony. His generous work as a teacher at Tanglewood, Harvard, and the New School for Social Research gained him a following of devoted musicians. As a scholar, he wrote more than sixty articles and essays on music, as well as five books. He traveled the world in an attempt to elevate the status of American music abroad, and to increase its popularity at home. Through these various commitments to music and to his country, Aaron Copland became one of the most important figures in twentieth-century American music. On December 2, 1990, Aaron Copland died in North Tarrytown, New York.

55. "Simple Gifts" from Appalachian Spring (Leonard Bernstein, conductor)

56. "Fanfare For The Common Man" (Eugene Goossens, Cincinnati Symphony)

George Gershwin was one of the most significant American composers of the 20th century, known for popular stage and screen numbers as well as classical compositions.SynopsisBorn on September 26, 1898, in Brooklyn, New York, George Gershwin dropped out of school and began playing piano professionally at age 15. Within a few years, he was one of the most sought after musicians in America. A composer of jazz, opera and popular songs for stage and screen, many of his works are now standards. Gershwin died immediately following brain surgery on July 11, 1937, at the age 38.

Early lifeGeorge Gershwin was born Jacob Gershowitz on September 26, 1898, in Brooklyn, New York. The son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, George began his foray into music at age 11 when his family bought a secondhand piano for George’s older sibling, Ira.

A natural talent, it was George who took it up and eventually sought out mentors who could enhance his abilities. He eventually began studying with the noted piano teacher Charles Hambitzer, and apparently impressed him; in a letter to his sister, Hambitzer wrote, “I have a new pupil who will make his mark if anybody will. The boy is a genius.”

Throughout his 23-year career, Gerswhin would continually seek to expand the breadth of his influences, studying under an incredibly disparate array of teachers, including Henry Cowell, Wallingford Riegger, Edward Kilenyi and Joseph Schillinger.

Early Career After dropping out of school at age 15, Gershwin played in several New York nightclubs and began his stint as a “song-plugger” in New York’s Tin Pan Alley.

After three years of pounding out tunes on the piano for demanding customers, he had transformed into a highly skilled and dexterous composer. To earn extra cash, he also worked as a rehearsal pianist for Broadway singers. In 1916, he composed his first published song, “When You Want 'Em, You Can't Get 'Em; When You Have 'Em, You Don't Want 'Em.”

SuccessesFrom 1920 to 1924, Gershwin composed for an annual production put on by George White. After a show titled “Blue Monday,” the bandleader in the pit, Paul Whiteman, asked Gershwin to create a jazz number that would heighten the genre’s respectability.

Legend has it that Gershwin forgot about the request until he read a newspaper article announcing the fact that Whiteman’s latest concert would feature a new Gershwin composition. Writing at a manic pace in order to meet the deadline, Gershwin composed what is perhaps his best-known work, “Rhapsody in Blue.”

During this time, and in the years that followed, Gershwin wrote numerous songs for stage and screen that quickly became standards, including “Oh, Lady Be Good!” “Someone to Watch over Me,” “Strike Up the Band,” “Embraceable You,” “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off” and “They Can’t Take That Away from Me.” His lyricist for nearly all of these tunes was his older brother, Ira, whose witty lyrics and inventive wordplay received nearly as much acclaim as George’s compositions.

In the 1920s, Gershwin spent time in Paris, which inspired his jazz-influenced orchestral composition An American Paris. Composed in 1928, An American Paris inspired the 1951 Oscar-winning movie musical by the same name, which was directed by Vincente Minnelli and starred Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron. A Broadway musical based on the film opened in 2014.

In 1935, a decade after composing “Rhapsody in Blue,” Gershwin debuted his most ambitious composition, “Porgy and Bess.” The composition, which was based on the novel “Porgy” by Dubose Heyward, drew from both popular and classical influences. Gershwin called it his “folk opera,” and it is considered to not only be Gershwin’s most complex and best-known works, but also among the most important American musical compositions of the 20th century.

Following his success with “Porgy and Bess,” Gershwin moved to Hollywood and was hired to compose the music for a film titled “Shall We Dance,” starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. It was while working on a follow-up film with Astaire that Gershwin’s life would come to an abrupt end.

Untimely deathIn the beginning of 1937, Gershwin began to experience troubling symptoms such as severe headaches and noticing strange smells.

Doctors would eventually discover that he had developed a malignant brain tumor. On July 11, 1937, Gershwin died during surgery to remove the tumor. He was only 38.

57. "Rhapsody in Blue"

Early lifeGeorge Gershwin was born Jacob Gershowitz on September 26, 1898, in Brooklyn, New York. The son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, George began his foray into music at age 11 when his family bought a secondhand piano for George’s older sibling, Ira.

A natural talent, it was George who took it up and eventually sought out mentors who could enhance his abilities. He eventually began studying with the noted piano teacher Charles Hambitzer, and apparently impressed him; in a letter to his sister, Hambitzer wrote, “I have a new pupil who will make his mark if anybody will. The boy is a genius.”

Throughout his 23-year career, Gerswhin would continually seek to expand the breadth of his influences, studying under an incredibly disparate array of teachers, including Henry Cowell, Wallingford Riegger, Edward Kilenyi and Joseph Schillinger.

Early Career After dropping out of school at age 15, Gershwin played in several New York nightclubs and began his stint as a “song-plugger” in New York’s Tin Pan Alley.

After three years of pounding out tunes on the piano for demanding customers, he had transformed into a highly skilled and dexterous composer. To earn extra cash, he also worked as a rehearsal pianist for Broadway singers. In 1916, he composed his first published song, “When You Want 'Em, You Can't Get 'Em; When You Have 'Em, You Don't Want 'Em.”

SuccessesFrom 1920 to 1924, Gershwin composed for an annual production put on by George White. After a show titled “Blue Monday,” the bandleader in the pit, Paul Whiteman, asked Gershwin to create a jazz number that would heighten the genre’s respectability.

Legend has it that Gershwin forgot about the request until he read a newspaper article announcing the fact that Whiteman’s latest concert would feature a new Gershwin composition. Writing at a manic pace in order to meet the deadline, Gershwin composed what is perhaps his best-known work, “Rhapsody in Blue.”

During this time, and in the years that followed, Gershwin wrote numerous songs for stage and screen that quickly became standards, including “Oh, Lady Be Good!” “Someone to Watch over Me,” “Strike Up the Band,” “Embraceable You,” “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off” and “They Can’t Take That Away from Me.” His lyricist for nearly all of these tunes was his older brother, Ira, whose witty lyrics and inventive wordplay received nearly as much acclaim as George’s compositions.

In the 1920s, Gershwin spent time in Paris, which inspired his jazz-influenced orchestral composition An American Paris. Composed in 1928, An American Paris inspired the 1951 Oscar-winning movie musical by the same name, which was directed by Vincente Minnelli and starred Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron. A Broadway musical based on the film opened in 2014.

In 1935, a decade after composing “Rhapsody in Blue,” Gershwin debuted his most ambitious composition, “Porgy and Bess.” The composition, which was based on the novel “Porgy” by Dubose Heyward, drew from both popular and classical influences. Gershwin called it his “folk opera,” and it is considered to not only be Gershwin’s most complex and best-known works, but also among the most important American musical compositions of the 20th century.

Following his success with “Porgy and Bess,” Gershwin moved to Hollywood and was hired to compose the music for a film titled “Shall We Dance,” starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. It was while working on a follow-up film with Astaire that Gershwin’s life would come to an abrupt end.

Untimely deathIn the beginning of 1937, Gershwin began to experience troubling symptoms such as severe headaches and noticing strange smells.

Doctors would eventually discover that he had developed a malignant brain tumor. On July 11, 1937, Gershwin died during surgery to remove the tumor. He was only 38.

57. "Rhapsody in Blue"